Think of someone who’s wildly successful in one field. Now imagine that same person being equally brilliant in three or four completely different areas. Sounds unlikely, right? Yet history is filled with these exceptional minds who refused to be confined to a single path.

We live in an age that celebrates specialization. You pick a lane and stick to it. Yet some of the most remarkable people who ever lived took the opposite approach, mastering everything from painting to physics, from diplomacy to invention. Their stories challenge the very notion that we should limit ourselves to one talent or interest.

Leonardo da Vinci: The Original Renaissance Man

Let’s be real, when you think of someone brilliant at multiple things, Leonardo probably comes to mind first. Born in 1452 near the small town of Vinci in Italy, this illegitimate son of a notary became arguably the most versatile genius in recorded history. His famous paintings like the Mona Lisa and The Last Supper are just the tip of an enormous intellectual iceberg.

Leonardo is renowned not only for his paintings but also in the fields of civil engineering, chemistry, geology, geometry, hydrodynamics, mathematics, mechanical engineering, optics, physics, pyrotechnics, and zoology. He conceptualized helicopters and parachutes centuries before the technology existed to build them. He studied nature, mechanics, anatomy, physics, architecture, weaponry and more, often creating accurate, workable designs for machines like the bicycle, helicopter, submarine and military tank that would not come to fruition for centuries.

His anatomical drawings remain some of the most detailed studies of the human body ever created. His findings from anatomical studies were recorded in famous anatomical drawings, which are among the most significant achievements of Renaissance science, based on a connection between natural and abstract representation. What made Leonardo truly unique was his belief that art and science were two sides of the same coin, each informing and enriching the other.

Benjamin Franklin: America’s Multitalented Founding Father

Here’s the thing about Benjamin Franklin: most Americans know him from the hundred dollar bill, but few appreciate the staggering breadth of his achievements. Franklin was an American polymath: a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher and political philosopher. Born in 1706 as the tenth son of a soap and candle maker, Franklin had barely two years of formal schooling.

Benjamin Franklin was many things in his lifetime: a printer, a postmaster, an ambassador, an author, a scientist, and a Founding Father. Above all, he was an inventor, creating solutions to common problems, innovating new technology, and even making life a little more musical. He invented bifocals, the lightning rod, and the Franklin stove. Professor Leo LeMay credited Franklin with adopting four words we all know today when it comes to electricity: battery, positive, negative, and charge.

As a diplomat, Franklin secured crucial French support during the American Revolution. He helped draft both the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. He was a successful newspaper publisher, founded libraries, organized fire departments, and even invented swim fins as an eleven year old boy. He never patented his inventions; in his autobiography he wrote that as we enjoy great advantages from the inventions of others, we should be glad of an opportunity to serve others by any invention of ours freely and generously.

Isaac Newton: Gravity, Light, and the Mint

Newton might be most famous for that apple allegedly falling on his head, but his intellectual empire stretched far beyond physics. Isaac Newton was an English physicist, mathematician, astronomer, theologian, natural philosopher and alchemist. His treatise Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica, published in 1687, described universal gravitation and the three laws of motion, laying the groundwork for classical mechanics.

What many don’t realize is that Newton spent a significant portion of his later life as Master of the Royal Mint, where he personally pursued counterfeiters and reformed England’s coinage system. He was deeply interested in alchemy and theology, writing more on religious subjects than on natural philosophy. In a 2005 poll of the Royal Society of who had the greatest effect on the history of science, Newton was deemed more influential than Albert Einstein. His mathematical innovations alone, including the development of calculus, would have secured his place in history.

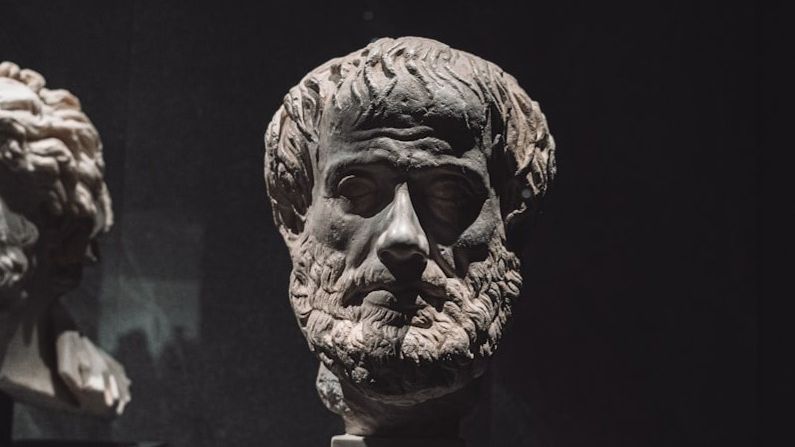

Aristotle: Philosophy’s Ancient Giant

Jumping back to ancient Greece, Aristotle stands out as someone whose interests knew no boundaries. Born in 384 BC, he studied under Plato before becoming tutor to Alexander the Great. Honestly, that’s already an impressive resume before we even get to his actual work.

While his teacher Plato and Socrates share a similar philosophical lineage, Aristotle was the most polymathic of the trio. He was interested in every possible science practiced in his time and his works cover many subjects: physics, biology, zoology, metaphysics, logic, ethics, aesthetics, poetry, theater, music, rhetoric, linguistics, and politics. He founded the Lyceum and essentially created the scientific method as we understand it today.

His observations on biology remained authoritative for nearly two thousand years. He wrote extensively on political systems, developed formal logic, and established literary criticism as a discipline. The sheer scope of his intellectual curiosity remains breathtaking even by today’s standards.

Marie Curie: Breaking Barriers in Multiple Sciences

Marie Curie didn’t just break the glass ceiling; she shattered it in not one but two scientific disciplines. Born Maria Sklodowska in Warsaw in 1867, she moved to Paris to study physics and mathematics, facing financial hardship and gender discrimination at every turn.

Marie Curie is named among the most impactful individuals, both contemporary and historical, who have been generalists including Elon Musk, Steve Jobs, Richard Feynman, Ben Franklin, Thomas Edison, Leonardo Da Vinci. She became the first woman to win a Nobel Prize, the first person to win Nobel Prizes in two different sciences (Physics in 1903 and Chemistry in 1911), and the first woman professor at the University of Paris.

Her pioneering research on radioactivity literally created a new field of science. She discovered two elements, polonium and radium, developed mobile X-ray units during World War I, and established the foundations for cancer treatment. She balanced groundbreaking laboratory work with raising two daughters, one of whom also won a Nobel Prize. Her legacy extends far beyond her scientific achievements into the realm of social change.

Thomas Jefferson: Architect of a Nation and Buildings

The principal author of the Declaration of Independence was far more than just a politician. Jefferson was an accomplished architect who designed his home Monticello and founded the University of Virginia, creating its distinctive campus layout. US President John F. Kennedy once claimed at a gathering of 49 Nobel laureates that he believed it was the most talented and knowledgeable people ever assembled in the White House, except perhaps on the days when Thomas Jefferson dined alone.

Jefferson was a skilled violinist, a paleontologist who excavated mastodon bones, a horticulturist who introduced numerous plant species to America, and an inventor who created the swivel chair and improved the design of the moldboard plow. He spoke multiple languages fluently, amassed a library of thousands of volumes that became the core of the Library of Congress, and kept detailed weather records for decades.

His agricultural innovations helped shape American farming. He served as diplomat to France, Secretary of State, Vice President, and two terms as President. Jefferson, like others equally famous, may be saluted as the last of the Renaissance men. His activities as a farmer, a musician and composer, an architect, an archaeologist, or an inventor are generally noted only in passing.

John von Neumann: The Human Computer

If anyone comes close to Leonardo’s breadth in the modern era, it might be John von Neumann. Born in Budapest in 1903, he displayed mathematical genius from childhood. Von Neumann had a photographic memory that allowed him to recite entire books verbatim years after reading them.

John von Neumann is often regarded as a quintessential modern polymath. His achievements spanned mathematics, physics, computer science, and economics, leaving a legacy that continues to shape contemporary thought. He co-founded the mathematical discipline of game theory, revolutionizing economics and decision-making processes. His conceptualization of the stored-program computer architecture, known as the von Neumann architecture, became the foundation of modern computing.

He contributed to quantum mechanics, set theory, and was instrumental in the Manhattan Project. He could solve complex differential equations in his head while driving recklessly to parties. His work laid the groundwork for everything from weather prediction to artificial intelligence. The architecture of virtually every computer you use today is based on his designs.

Galileo Galilei: Challenging the Heavens

Galileo didn’t just look at the stars; he fundamentally changed how humanity understood its place in the universe. Born in Pisa in 1564, he excelled as an astronomer, physicist, engineer, and philosopher. Known as the father of modern science, Galileo contributed to physics, astronomy, and mathematics. His inventions, such as the improved telescope, and his advocacy for the heliocentric model of the solar system demonstrate his ability to challenge prevailing dogmas.

He improved the telescope and used it to discover Jupiter’s moons, observe the phases of Venus, and study sunspots. His experiments with falling objects and pendulums laid the foundation for classical mechanics. He designed military compasses and wrote on everything from music theory to tidal mechanics.

His willingness to defend scientific truth, even when it brought him into conflict with the Catholic Church, made him a symbol of intellectual courage. He spent his final years under house arrest, yet continued his scientific work, producing some of his most important writings on motion and strength of materials.

Émilie du Châtelet: Mathematics and the Enlightenment

In eighteenth-century France, women weren’t supposed to be scholars. Émilie du Châtelet didn’t get that memo. She was the 18th-century polymath who defied societal norms. She translated Newton’s Principia Mathematica while pregnant at 42. She engaged in a passionate love affair with Voltaire.

Her brilliant mind led her to make groundbreaking contributions to energy conservation. She had to deal with the complexities of being a woman in a male-dominated field. She wore men’s clothing to gain access to scientific gatherings. Her translation of Newton’s work into French, which included her own commentary and mathematical explanations, remains the standard French version today.

She conducted experiments in physics, wrote philosophical treatises, and contributed to the development of concepts that would later become the law of conservation of energy. She corresponded with the leading intellectuals of her day and hosted a salon that became a center of Enlightenment thought. Her life reminds us how many brilliant minds were suppressed simply because of their gender.

George Washington Carver: Agricultural Revolution

Born into slavery around 1864, George Washington Carver overcame unimaginable obstacles to become one of America’s most influential scientists. Born into slavery in 1864, he became a renowned agricultural scientist. He developed over 300 products from peanuts and introduced crop rotation techniques that saved countless farms from financial ruin. Carver was the first African American to earn a Bachelor of Science degree.

Beyond his agricultural innovations, Carver was an accomplished painter whose artwork was exhibited at the World’s Fair. He was a skilled pianist and a beloved teacher at Tuskegee Institute. He would invent a mobile classroom called the Jesup wagon to educate farmers. His methods of crop rotation and soil improvement transformed Southern agriculture and helped thousands of farmers escape the poverty trap of cotton monoculture.

He developed products ranging from dyes to plastics to cosmetics, all from agricultural materials. He advised Presidents and industrialists, yet chose to remain a teacher, believing education was the key to progress. His gentleness and humility masked a fierce intellect and determination.

Archimedes: Ancient Engineering Genius

Long before the Renaissance, ancient Syracuse produced one of history’s greatest polymaths. Archimedes, born in 287 BCE in Syracuse, was a polymath of the ancient world. He’s remembered for many inventions, including the compound pulley and a claw-like device for sinking enemy ships. He’s most famous for his Eureka moment in the bathtub that led to groundbreaking insights on buoyancy.

He laid the foundations for calculus nearly two thousand years before Newton and Leibniz. His work on the geometry of spheres and cylinders was so important to him that he requested these shapes be inscribed on his tomb. He invented the Archimedes screw, still used today for moving water, and designed war machines so effective they delayed Roman conquest for years.

Archimedes supposedly used giant mirrors to concentrate sunlight and set Roman ships on fire during the Siege of Syracuse. Whether or not the burning mirrors actually worked, his genius for practical application of mathematical principles was undeniable. He moved effortlessly between pure theory and mechanical invention.

René Descartes: I Think, Therefore I Excel

René Descartes was a French polymath of the 17th century who developed brilliant concepts in philosophy and mathematics. He’s most famous for his literary works, such as Cogito, ergo sum, which laid the foundations for analytic geometry. His philosophical method of systematic doubt revolutionized Western thought.

Descartes made fundamental contributions to algebra and geometry, inventing the Cartesian coordinate system that bears his name. He studied optics and meteorology, developing theories about light refraction and rainbow formation. He wrote extensively on physiology and the nature of human emotions.

His influence on both philosophy and mathematics cannot be overstated. The way we graph equations today is essentially Descartes’ invention. His insistence on clear, logical thinking as the basis for knowledge shaped the entire Enlightenment. He even found time to tutor Queen Christina of Sweden in philosophy, though the early morning lessons in cold Stockholm allegedly contributed to his death from pneumonia.

Samuel Morse: From Canvas to Code

Before Samuel Morse revolutionized communication, he pursued a completely different dream. As a student at Yale, Samuel Morse studied philosophy and math, but dreamed of a career as an artist of great history paintings. After that dream cooled, he went on to pursue his interest in the burgeoning field of electromagnetics. Morse would go on to develop both the telegraph and the Morse code, sending the biblical line What hath God wrought from the US Capitol to Baltimore with his new invention.

Morse trained under Benjamin West at London’s Royal Academy of Arts and co-founded the National Academy of Design in Manhattan, yet his career as an artist is largely overshadowed by his contributions to communications. He created impressive portrait paintings and studied under some of the finest artists of his era.

His shift from art to invention wasn’t a complete departure. The observational skills and attention to detail he developed as an artist served him well in his scientific pursuits. The telegraph revolutionized how information traveled, essentially creating our modern connected world. He proved that talents in one field can unexpectedly enhance achievements in another.

Maria Sibylla Merian: Nature’s Artist-Scientist

In the seventeenth century, most people thought insects spontaneously generated from mud. Maria Sibylla Merian knew better. A 17th-century naturalist and botanist, Merian was one of the first European scientists to directly observe insects. When she started her research, insects were still commonly referred to as beasts of the devil. Her most influential studies detailed the metamorphosis of caterpillars into butterflies. She penned a two-volume book on caterpillars and is today considered one of the pioneers of the field of entomology.

Before her scientific investigations, Merian first earned acclaim as a botanical artist, publishing a three-volume series of illustrated plates of flowers in 1675. Her precise, beautiful illustrations were based on direct observation, revolutionary for her time. She traveled to Dutch Suriname at age 52 to study tropical insects, an extraordinary journey for any person in that era, let alone a woman traveling largely alone.

Her work bridged art and science perfectly. Her illustrations were scientifically accurate enough to aid identification while being beautiful works of art. She documented insect lifecycles with unprecedented detail, helping establish entomology as a serious scientific discipline.

Santiago Ramón y Cajal: Drawing the Brain

Known as the father of modern neuroscience, Spaniard Cajal was the first to suggest that individual cells structure the brain and, in the 1890s, created detailed drawings to illustrate his microscope-aided findings. His Nobel Prize-winning depictions are, even now, valuable sources of neurological information, and attest to Cajal’s artistic affinities as he originally set out to be an artist before his father pushed him toward medicine.

His father, a surgeon, wanted him to pursue medicine, but young Santiago dreamed of being an artist. The compromise turned out to be perfect. His artistic talent allowed him to create drawings of neurons so detailed and accurate that they’re still used in textbooks today. He essentially mapped the nervous system through a combination of scientific observation and artistic skill.

He wrote books, took up photography as a serious hobby, and even wrote science fiction stories. His ability to visualize the microscopic structures of the brain and render them comprehensibly changed our entire understanding of how the nervous system functions. His life shows how supposedly opposite talents can combine to create something neither could achieve alone.

A Legacy That Inspires

These fifteen remarkable individuals share something beyond their obvious brilliance. They refused to accept artificial boundaries between disciplines. In today’s rapidly changing and interconnected world, the value of polymaths cannot be overstated. Their ability to bridge gaps between disciplines, synthesise knowledge from diverse sources, and approach problems from multiple angles makes them indispensable assets in tackling complex challenges. As we face increasingly complex global issues that transcend traditional boundaries, the need for individuals with a broad knowledge base becomes even more crucial.

Looking at their lives, a pattern emerges. These weren’t people who dabbled superficially in many areas. They achieved genuine mastery across multiple fields through relentless curiosity, disciplined work, and the willingness to see connections others missed. They prove that human potential is far more expansive than our modern culture of specialization suggests.

The world faces challenges that don’t fit neatly into academic departments or professional categories. Climate change, artificial intelligence, global health, and social inequality all require thinking that crosses boundaries. Perhaps we need more polymaths now than ever before. What would you explore if you stopped limiting yourself to just one path?