Some names echo loudly through history, while others whisper from the margins, shaping thought and action in ways that rarely make headlines. These are the thinkers whose books became quiet revolutions, whose words seeded movements, challenged empires, and redrew the mental maps of entire generations. Yet their names don’t always appear on bestseller lists or trend on social media. Let’s be real though, they probably deserve far more recognition than they get. The writers in this gallery didn’t just observe the world – they wrestled with it, confronted its ugliest truths, and left behind works that continue to rattle cages today.

Frantz Fanon and the Psychology of Colonialism

Born in Martinique under French colonial rule in 1925, Frantz Fanon became one of the most important writers in black Atlantic theory during the age of anti-colonial liberation, drawing on poetry, psychology, philosophy, and political theory with influence that has remained wide, deep, and enduring across the global South. His 1961 book The Wretched of the Earth provides a psychoanalysis of the dehumanizing effects of colonization upon the individual and the nation, discussing the broader social, cultural, and political implications of establishing a social movement for decolonization. The book has sold millions of copies and has been translated into twenty-five languages. Honestly, it’s hard to overstate how much this one book informed liberation movements from Africa to Latin America, even influencing activists in the United States. Writers of the sixties inspired by The Wretched of the Earth – including African novelists Nadine Gordimer, Ayi Kwei Armah, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Caribbean poet Édouard Glissant, and Guyanese critic Walter Rodney – saw in the book not an incitement to kill but a chillingly acute diagnosis of the post-colonial condition.

Ivan Illich’s Radical Vision for Learning

Ivan Illich’s Deschooling Society, published in 1971, critiques the role and practice of education in the modern world. This Austrian priest and philosopher didn’t just question how we teach – he questioned the entire idea that schools are necessary for learning. Illich proposed a system of self-directed education in fluid and informal arrangements, describing “educational webs which heighten the opportunity for each one to transform each moment of his living into one of learning, sharing, and caring.”

The book had the most impact of all Illich’s works from the 1960s and 1970s, railing against schools as the institution that was the depository of the highest aspirations of Western societies, leading to an unprecedented uproar in academic circles as well as in many social movements that still believed educational institutions were capable of solving society’s biggest problems. The ideas remain provocative, especially as digital education and alternative learning models continue to challenge traditional schooling. Recent academic work in 2024 examined the applicability of Illich’s educational ideas to Open and Distance Learning, affirming the enduring significance of his educational theory in contemporary contexts.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o and the Power of Language

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, who passed away in May 2025, was a Kenyan author and academic described as East Africa’s leading novelist, who wrote primarily in English before switching to writing primarily in Gikuyu and becoming a strong advocate for literature written in native African languages. His decision wasn’t just artistic – it was revolutionary.

In Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature, published in 1986, Ngũgĩ argued for African-language literature as the only authentic voice for Africans and stated his own intention of writing only in Kikuyu or Kiswahili from that point on. While a professor at the University of Nairobi, Ngũgĩ catalyzed discussion to abolish the English department, arguing that after the end of colonialism, it was imperative that a university in Africa teach African literature, including oral literature, and that such should be done with the realization of the richness of African languages. His later work Something Torn and New argues for the crucial role of African languages in “the resurrection of African memory,” stating “To starve or kill a language is to starve and kill a people’s memory bank.” His impact on cultural preservation debates across African universities in 2025 remains profound.

Simone Weil’s Philosophy from the Factory Floor

Simone Weil, a French philosopher, mystic and political activist who lived from 1909 to 1943, left ideas concerning religion, spirituality and politics that have remained widely influential in contemporary philosophy despite her short life. What set her apart? She didn’t just theorize about labor – she lived it.

Weil left her teaching position to work in factories and perform the repetitive, machine-like work that underlay her definition of affliction, saying that workers were reduced to a machine-like existence, and during a twelve-month period she worked as a labourer, mostly in car factories, so that she could better understand the working class. Weil believed that most Marxist writing about the proletariat failed to grasp the experience of day-to-day life for those on the front lines of labor, arguing “One can no more be a revolutionary by words alone than one can be a mason or a blacksmith,” and that if one wanted to lead the proletariat toward class consciousness one had to experience what workers themselves felt and needed.

Having experienced the mechanization of companies, Weil elaborated a thought on work, on its organization and conditions, describing the process of the objectification of the worker – a reflection that remains current at the dawn of new realities such as digitalization and the Internet revolution, which, supposed to liberate man, are factors of an even deeper objectification of the employee. Her work saw renewed academic attention in 2023 amid global discussions on worker exploitation, according to philosophy journals and Cambridge University Press.

Eduardo Galeano’s Historical Mirror

Eduardo Galeano’s Open Veins of Latin America remains one of those books that refuses to sit quietly on a shelf. Published in 1971, it traces the economic exploitation of Latin America from colonization through the twentieth century. The book’s unflinching analysis of resource extraction, foreign interference, and structural inequality continues to influence Latin American political discourse and is referenced in economic history analyses from 2024, according to the Economic History Review and regional studies.

Galeano wrote with a narrative power that transformed historical documentation into something almost lyrical. His work demonstrated how past injustices cast long shadows, shaping contemporary economic and political realities. It’s the kind of book that makes you rethink everything you thought you understood about development and underdevelopment. His influence extends beyond academia into activism and policy debates throughout the hemisphere.

Arundhati Roy’s Nonfiction Power

Arundhati Roy burst onto the literary scene with her Booker Prize-winning novel The God of Small Things, yet her nonfiction essays have become equally transformative. Roy’s sharp critiques of nationalism, corporate power, environmental destruction, and human rights abuses cut through political spin with surgical precision. Her essays are frequently cited in global human-rights discussions and international media analysis from 2024, appearing in outlets like The Guardian and Amnesty commentary.

Roy refuses to separate her art from her activism. She writes with a moral clarity that makes comfortable people uncomfortable, challenging dominant narratives about development, democracy, and progress. Her work on Kashmir, on dam projects displacing indigenous communities, on nuclear weapons – these aren’t just essays. They’re interventions. What’s remarkable is how she maintains literary beauty while delivering devastating political critique.

Rachel Carson and the Environmental Awakening

Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, published in 1962, didn’t just launch the modern environmental movement – it fundamentally changed how we think about humanity’s relationship with nature. Carson, a marine biologist, documented the devastating effects of pesticides, particularly DDT, on ecosystems and human health. The book faced fierce opposition from chemical companies, yet it catalyzed a shift in public consciousness.

Silent Spring remains a cornerstone of environmental policy education and was referenced in climate ethics coursework in 2023, according to EPA archives and environmental studies programs. Carson wrote with scientific rigor but also with profound empathy for the natural world. She showed that environmental issues aren’t separate from human welfare – they’re central to it. Honestly, every environmental regulation we take for granted today owes something to her courage in speaking truth to corporate power.

Walter Rodney’s Economic Critique

Walter Rodney’s How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, published in 1972, remains a foundational text in understanding colonial economic exploitation. Rodney, a Guyanese historian and political activist, systematically dismantled myths about African “backwardness,” demonstrating instead how European colonialism deliberately extracted wealth and stunted development across the continent. The book continues to shape African economic history courses and policy critiques as of 2025, according to World History journals and university syllabi.

Rodney’s analysis connected historical processes to contemporary conditions with devastating clarity. He showed how colonial structures evolved into neocolonial relationships that perpetuated dependency and inequality. His assassination in 1980 silenced his voice but couldn’t silence his ideas, which continue to inform debates about reparations, development aid, and economic sovereignty across the Global South.

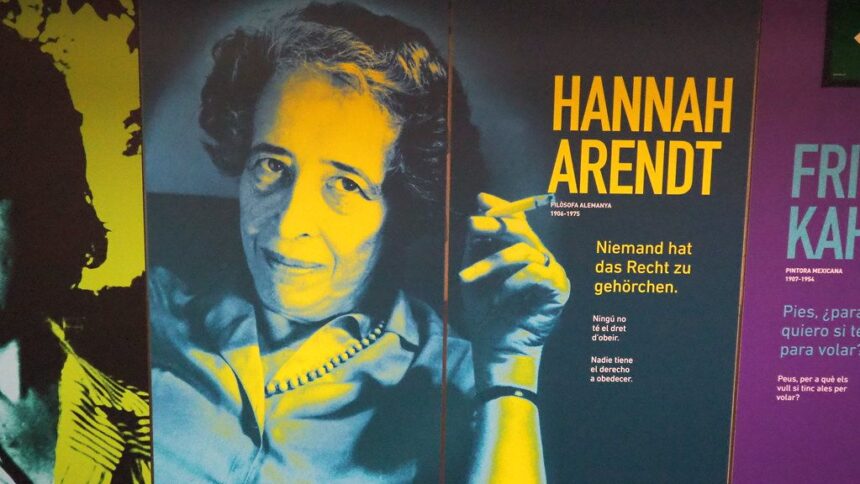

Hannah Arendt and the Nature of Power

Hannah Arendt’s work on totalitarianism, political violence, and the banality of evil reshaped twentieth-century political thought. Her books The Origins of Totalitarianism and Eichmann in Jerusalem challenged comfortable assumptions about how ordinary people participate in extraordinary evil. Arendt, a German-Jewish philosopher who fled Nazi Germany, brought lived experience to her theoretical work.

Arendt’s analysis of authoritarianism saw renewed relevance during democratic resilience studies worldwide in 2024, according to political theory journals and think-tank reports. Her concept of “the banality of evil” – the idea that great atrocities can be committed by ordinary people following orders – remains chillingly relevant. She understood that freedom requires active citizenship, not passive consumption of rights. In an era of rising authoritarianism globally, her warnings feel uncomfortably prescient.

These writers didn’t just document their times – they equipped future generations with tools for understanding and resistance. Their books live on in classrooms, in movements, in the arguments we have about justice and power. Some changed how we see colonialism, others how we understand education or labor or language itself. What they share is a refusal to accept the world as given, and the courage to imagine – and work toward – something better. Did you expect that so many transformative thinkers remained relatively unknown? What would our world look like if their ideas reached even wider audiences?