You know that feeling when you crack open a book and the very first sentence grabs you by the collar? It’s rare, honestly. Most books ease you in gently, maybe too gently. But then there are those opening lines that hit different. They make you forget you’re holding a book at all. You’re just there, pulled into another world before you even realize what happened.

Some writers have this uncanny ability to hook you immediately. One sentence, and suddenly you’re canceling plans because you need to know what happens next. Let’s dive into some of those magnetic opening lines that refuse to let go.

The Stranger by Albert Camus

“Mother died today. Or maybe yesterday; I can’t be sure.” Right from the start, you’re thrown off balance. The casual uncertainty about his own mother’s death is unsettling in the best way. It tells you everything about the narrator without explaining a thing. You immediately want to understand this person who seems so detached from something so fundamental.

Camus wastes zero words here. The bluntness creates this weird discomfort that’s impossible to ignore. You’re already questioning the narrator’s emotional state, his relationship with his mother, his entire perspective on life. That’s a lot of weight for two short sentences to carry, but somehow it works perfectly.

The simplicity is deceptive. There’s something deeply wrong lurking beneath those plain words, and you can feel it. It’s the literary equivalent of meeting someone at a party who seems normal until they say something that makes you think, “Wait, what?”

1984 by George Orwell

“It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen.” Such a small detail, but it changes everything. Clocks don’t strike thirteen. That one wrong number tells you the world you’re entering operates by different rules. It’s brilliant because it’s so understated.

Orwell could have started with some dramatic description of totalitarianism or surveillance. Instead, he went with something quietly impossible. The contradiction between “bright” and “cold” already sets up the doublethink that permeates the entire novel. Everything feels slightly off from the very beginning.

You barely notice you’re being pulled in because the sentence seems so ordinary at first glance. Then your brain catches up and you realize nothing about this world is going to be normal. That thirteen haunts you.

The Metamorphosis by Franz Kafka

“As Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from uneasy dreams he found himself transformed in his bed into a gigantic insect.” No build-up, no explanation, just boom – you’re an insect now, deal with it. The matter-of-fact tone makes the absurdity even more jarring.

Most writers would spend chapters building to such a transformation. Kafka just drops you into it like it’s a regular Tuesday. The casualness is what makes it so disturbing and captivating. You’re immediately wondering how this happened, why it happened, and how anyone could describe it so calmly.

It’s hard to say for sure, but this might be one of the most unforgettable opening lines in all of literature. You can’t un-read it. The image of a man waking up as a bug is permanently lodged in your mind after those first words.

Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier

“Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again.” There’s something haunting in that simplicity. The word “again” suggests a return to somewhere significant, somewhere maybe you shouldn’t go back to. It’s nostalgic and ominous at the same time.

You immediately want to know what Manderley is and why the narrator can only return in dreams. There’s loss baked into that sentence, and mystery. The past tense combined with the dream state creates this eerie distance that pulls you in. What happened at Manderley?

Du Maurier understood that sometimes the most effective hook is just a whisper of something unfinished. You’re already emotionally invested before you know a single detail about the story. That’s the power of suggestion done right.

Catch-22 by Joseph Heller

“It was love at first sight.” Seems romantic, right? Then you read the next line and realize he’s talking about a chaplain. Heller immediately subverts your expectations and sets the tone for the absurdist satire that follows. You know you’re in for something unpredictable.

The opening plays with conventional romance language in a military setting, which is exactly the kind of twisted logic that defines the entire novel. It’s playful and disorienting, making you question everything that comes next. What kind of book starts a war story like a romance?

Heller’s genius is making you laugh and feel uncomfortable simultaneously. That first sentence seems innocent until you realize nothing in this book will be straightforward. The absurdity starts immediately and never lets up.

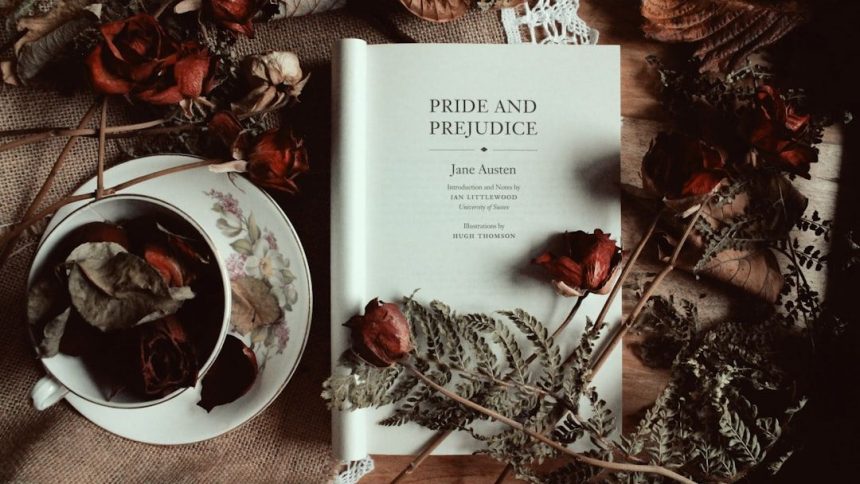

Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

“It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.” The irony is so sharp you can practically hear Austen smirking as she wrote it. She’s mocking the very society she’s about to depict.

That “truth universally acknowledged” is obviously not universal at all. It’s what society wants to believe, especially mothers with unmarried daughters. Austen sets up the entire social commentary of the novel in one perfectly constructed sentence. You’re already in on the joke.

The formal, declarative tone makes the satire even more effective. She’s not shouting her criticism; she’s stating it as fact with a straight face. It’s the literary equivalent of a perfectly timed eye roll, and it’s impossible not to appreciate.

Moby-Dick by Herman Melville

“Call me Ishmael.” Three words that have become iconic. It’s direct, mysterious, and strangely inviting. He doesn’t say “My name is Ishmael” – he says “call me” Ishmael, suggesting maybe that’s not even his real name.

There’s an intimacy in that phrasing, like he’s speaking directly to you, the reader. He’s inviting you into his confidence while simultaneously keeping secrets. You’re hooked because you want to know who this person really is and why he’s choosing to be called Ishmael.

Melville could have started with the whale or the ocean or Ahab. Instead, he started with a simple introduction that’s somehow more compelling than any action scene could be. The mystery is in the simplicity.

Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy

“Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” This philosophical observation immediately tells you what kind of story you’re about to read. Tolstoy isn’t interested in happy families. He’s diving into the messy, unique ways people fall apart.

The sentence works as both a thesis statement and a hook. You know this will be about unhappiness, but the promise that it’s a unique kind of unhappiness makes you curious. How exactly will this family be unhappy? What’s their particular flavor of dysfunction?

It’s also deeply human and relatable. Most of us have experienced or witnessed family drama, and Tolstoy is essentially promising to show us something we haven’t seen before. That’s an offer readers can’t refuse.

The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

“In my younger and more vulnerable years my father gave me some advice that I’ve been turning over in my mind ever since.” Nick Carraway is immediately established as reflective and slightly uncertain. He’s been thinking about this advice for years, which suggests it’s both important and complicated.

The phrase “more vulnerable years” is interesting because it implies he’s less vulnerable now, more hardened. Something happened to change him. You want to know what, and you want to know what advice could stick with someone that long. Fitzgerald makes you curious about both the narrator and the story he’s about to tell.

There’s also a sense that this is a story being told in retrospect, with the wisdom of hindsight. Nick isn’t just telling you what happened; he’s telling you what it meant. That promise of meaning makes the opening irresistible.

Closing Thoughts

These opening lines prove that the beginning of a story is everything. One sentence can create a mood, establish a voice, introduce a character, and hook a reader completely. The best ones make you forget you’re reading at all. You’re just there, in the moment, desperate to know what comes next.

Let’s be real, most books don’t pull this off. But when they do, it’s magic. These lines have stayed with readers for decades, some for over a century. They’ve become part of our cultural conversation because they understood something fundamental about storytelling: start strong, make it count. What opening line grabbed you and never let go? Tell us in the comments.