History has a funny way of proving critics wrong. Some of the world’s most celebrated artworks – pieces that now command millions at auction and draw endless crowds at museums – were once dismissed as garbage, ridiculed by experts, and mocked by the public. It’s almost poetic, really. The very things people once hated are now the treasures we protect behind velvet ropes and climate-controlled glass.

What changed? Sometimes it’s just that people needed time to catch up. Other times, the world itself had to shift before we could see what the artist was trying to show us. Let’s dive into some of the most stunning reversals in art history, where hate turned into love and rejection became worship.

Vincent van Gogh’s “The Starry Night” – A Failure in His Own Eyes

Van Gogh himself thought this painting was a failure. He wrote to his brother Theo calling it inadequate, and critics at the time either ignored it or dismissed it as the work of a madman. The swirling sky, the vibrant colors, the emotional intensity – none of it matched what people expected from landscape painting in 1889.

Today, “The Starry Night” is one of the most recognizable images in all of art. It hangs in the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and its value is considered immeasurable. People travel from across the globe just to stand in front of it. Van Gogh sold only one painting during his lifetime. Now his works routinely fetch over a hundred million dollars.

The irony cuts deep. The artist died thinking he’d failed, never knowing that future generations would see genius where his contemporaries saw chaos.

Édouard Manet’s “Olympia” – A Scandal That Shocked Paris

When Manet unveiled “Olympia” at the 1865 Paris Salon, the reaction was visceral disgust. Critics called it vulgar, obscene, and offensive. The painting shows a nude woman lying on a bed, staring directly at the viewer with a challenging gaze. People were outraged. Guards had to be posted because visitors threatened to damage it.

The problem wasn’t just nudity – classical nudes were everywhere. It was the way Manet presented her. This wasn’t some mythological goddess. This was a real woman, a courtesan, painted without idealization or apology. The art establishment couldn’t handle it.

Fast forward to today, and “Olympia” is considered a masterpiece that changed the course of modern art. It hangs in the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, studied and celebrated. What once provoked moral panic is now seen as a bold statement about class, sexuality, and the male gaze.

Igor Stravinsky’s “The Rite of Spring” – A Riot in the Theater

Okay, this one’s technically music and ballet, but it deserves a spot here because the reaction was legendary. When Stravinsky’s composition premiered in Paris in 1913, the audience literally rioted. Fistfights broke out in the theater. People screamed, booed, and threw objects at the stage.

The dissonant chords, irregular rhythms, and primal choreography were too much for the refined Parisian audience. They expected grace and beauty. Instead, they got raw, pagan energy that felt like an assault on their senses. Critics called it barbaric noise.

Today, “The Rite of Spring” is considered one of the most influential works of the twentieth century. It revolutionized music and dance, and it’s performed constantly around the world. The riot is now part of the legend, proof that truly innovative art often provokes before it inspires.

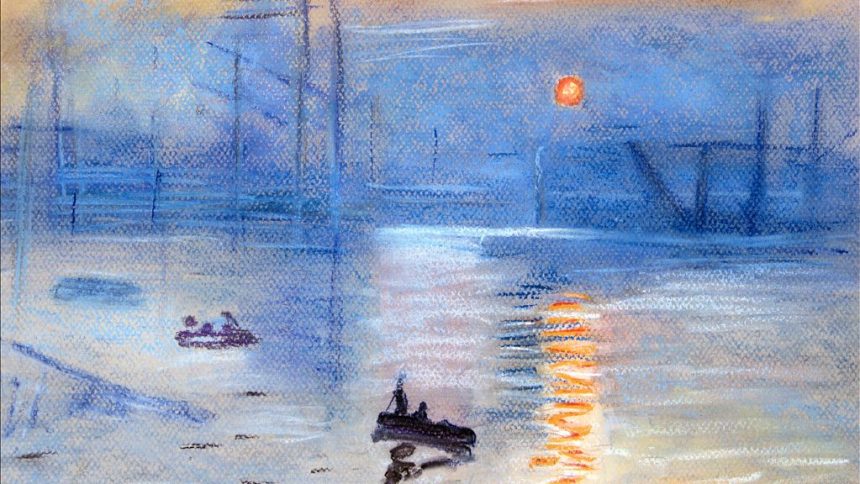

Claude Monet’s “Impression, Sunrise” – The Painting That Named an Entire Movement

A critic looked at this painting in 1874 and sneered. He sarcastically called the exhibition of Monet and his contemporaries the “Exhibition of the Impressionists,” using the word as an insult. He meant it to suggest that the work was unfinished, just a vague impression rather than proper art.

The establishment hated how loose and sketchy it looked. Where were the clear lines? Why were the colors so bright and unmixed? It violated all the rules taught at the prestigious art academies. Most critics dismissed the entire group as amateurs.

Of course, that insult became the name of one of art history’s most beloved movements. Impressionism changed everything. And “Impression, Sunrise” – that mocked, dismissed painting – is now worth tens of millions and hangs in the Musée Marmottan Monet in Paris. The joke’s on those critics.

Gustave Courbet’s “The Stone Breakers” – Too Real, Too Poor

Courbet painted common laborers breaking stones on a roadside in 1849. The art world was appalled. Why would anyone paint poor workers doing manual labor? Art was supposed to elevate, to show heroic scenes, mythology, portraits of the wealthy. This was just… reality. Boring, unglamorous reality.

Critics attacked it as socialist propaganda, ugly, and beneath the dignity of art. The refined gallery-goers of Paris didn’t want to look at sweating peasants when they could admire Greek gods or noble ladies. Courbet was essentially told to stay in his lane.

Tragically, the original painting was destroyed during World War II, but what remains are photographs and Courbet’s reputation as a pioneer of Realism. His insistence on painting everyday life paved the way for modern art. What seemed offensive then – showing the world as it actually is – became fundamental to how we understand art’s purpose.

Henri Matisse’s “Blue Nude” – Called Grotesque and Incompetent

When Matisse exhibited his “Blue Nude” in 1907, critics tore into it with remarkable cruelty. They called the proportions hideous, the colors absurd, and the overall effect revolting. One reviewer suggested Matisse had forgotten how to draw properly.

The painting shows a reclining female figure in shades of blue against a tropical background. The forms are simplified and distorted in ways that emphasize emotional impact over realistic representation. To the academic establishment, it looked like a child’s work, not a serious artist’s.

Today, Matisse is celebrated as one of the greatest colorists in art history. “Blue Nude” is recognized as a pivotal work in the development of modern art. The Baltimore Museum of Art proudly displays it as a centerpiece of their collection. Those critics who called it grotesque? Nobody remembers their names.

Pablo Picasso’s “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” – His Own Friends Hated It

Even Picasso’s close friends and fellow artists thought he’d gone too far with this one. When he showed them “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” in 1907, the reaction was shock and disappointment. The fragmented faces, the angular bodies, the aggressive composition – it seemed like a betrayal of everything art should be.

Matisse reportedly thought Picasso was mocking modern art. Another artist called it a hoax. The painting sat rolled up in Picasso’s studio for years because nobody wanted to buy it or show it. It depicted five nude figures with mask-like faces, breaking all conventions of perspective and form.

Now it’s considered the painting that launched Cubism and changed the trajectory of Western art forever. It hangs in the Museum of Modern Art in New York, valued in the hundreds of millions. What his friends saw as a disaster is now seen as a revolution.

Conclusion

The journey from hated to priceless tells us something profound about art, taste, and human nature. The works we now guard in climate-controlled museums were once rejected, mocked, even threatened with physical violence. What changed wasn’t the art itself, but our ability to see it. These artists were visionaries who paid the price for being too far ahead. They showed us new ways of seeing, feeling, and understanding, even when we weren’t ready.

Next time you encounter art that confuses or bothers you, maybe take a second look. History suggests that discomfort might be a sign something important is happening. What do you think – are we still making the same mistakes today? Tell us in the comments.