Picture this: a book so dangerous that authorities literally locked it away, fearing its words could corrupt minds and unravel society. Fast forward a few decades, and that same book sits on school reading lists, recommended by teachers and praised by critics worldwide. It’s one of literature’s greatest ironies.

Throughout history, countless books have faced the wrath of censors, governments, and moral guardians. Some were burned in public squares. Others were quietly removed from library shelves in the dead of night. The reasons varied wildly – from explicit content to political dissent, from religious blasphemy to simply challenging the status quo. Yet many of these once-forbidden works eventually became cornerstones of our literary heritage.

What transforms a banned book into a beloved classic? Sometimes it’s the passage of time softening society’s rigid boundaries. Other times, the very controversy that made a book dangerous is what makes it essential reading for future generations. Let’s explore the fascinating stories behind books that went from contraband to curriculum.

Ulysses by James Joyce

James Joyce’s masterpiece faced one of the most notorious banning sagas in literary history. When excerpts first appeared in an American magazine in 1918, authorities seized and burned copies, declaring the work obscene. The book’s stream-of-consciousness style and frank depictions of bodily functions and sexuality scandalized readers on both sides of the Atlantic.

For over a decade, Ulysses remained contraband in the United States and Britain. Copies were smuggled across borders like illegal goods. Random House eventually challenged the ban in court, and in 1933, Judge John M. Woolsey delivered a landmark ruling that the book had literary merit and wasn’t obscene. This decision fundamentally changed how courts evaluated literature.

Today, Ulysses stands as one of the twentieth century’s most influential novels. Scholars dissect its innovative narrative techniques. Universities worldwide include it in their modern literature courses. The book that was once burned is now analyzed paragraph by paragraph.

Joyce’s work opened doors for countless authors who followed. His victory proved that challenging traditional forms and exploring uncomfortable subjects could coexist with artistic excellence. What seemed like moral corruption in 1918 became recognized genius by the 1950s.

Lady Chatterley’s Lover by D.H. Lawrence

D.H. Lawrence knew his final novel would cause trouble. Published privately in Italy in 1928, Lady Chatterley’s Lover told the story of an aristocratic woman’s affair with her husband’s gamekeeper. The explicit sexual descriptions and use of four-letter words guaranteed instant controversy.

Britain banned the book immediately. For thirty years, it remained illegal to publish the complete, unexpurgated version in English-speaking countries. Publishers released sanitized editions, but Lawrence’s original text circulated underground, sometimes at exorbitant prices.

The 1960 obscenity trial in Britain became a cultural watershed moment. Penguin Books decided to publish the full text and deliberately provoked prosecution. The trial featured literary experts defending Lawrence’s artistic vision against prosecutors who seemed comically out of touch. When the jury found Penguin not guilty, it marked a turning point in censorship laws.

Lawrence’s novel is now studied for its nuanced exploration of class divisions, industrial society’s impact on human connection, and the redemptive potential of physical love. The sex scenes that once scandalized readers are understood as integral to Lawrence’s broader philosophical vision. Critics recognize it as a profound meditation on authenticity in modern life.

The Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger

Holden Caulfield’s weekend in New York City became one of literature’s most challenged books almost immediately after publication in 1951. Schools and libraries rushed to ban it, citing profanity, sexual references, and Holden’s generally cynical worldview. Parents worried the novel would corrupt impressionable teenagers.

The irony runs deep. Salinger wrote a book capturing adolescent alienation with painful honesty, and adults responded by trying to hide it from actual adolescents. Holden’s voice – raw, confused, desperately seeking authenticity – resonated with young readers precisely because it felt real, not sanitized.

Decades of banning attempts only amplified the book’s mystique. Teenagers found ways to read it anyway, often drawn specifically because authority figures said they shouldn’t. The more schools removed it from libraries, the more essential it seemed.

Today, The Catcher in the Rye appears on countless high school syllabi. Teachers use it to discuss adolescent psychology, post-war American culture, and literary voice. The profanity that once shocked censors now barely registers. What matters is Salinger’s unflinching portrayal of teenage confusion and the universal struggle to find meaning.

Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov

Few books have provoked as much discomfort as Nabokov’s 1955 novel about a middle-aged man’s obsession with a twelve-year-old girl. Multiple American publishers rejected the manuscript. The first edition appeared in Paris through Olympia Press, known for publishing erotic literature. British customs officials seized copies at the border.

The subject matter alone guaranteed moral outrage. A pedophile narrator? Critics and censors alike struggled with how to approach such transgressive material. Some saw pornography disguised as literature. Others recognized Nabokov’s linguistic brilliance and moral complexity.

Nabokov crafted an unreliable narrator whose eloquent prose masks monstrous behavior. Readers must navigate Humbert Humbert’s self-justifications while recognizing the horror of what he describes. It’s a high-wire act of literary ethics.

Modern readers understand Lolita as a masterclass in narrative technique and a searing critique of American culture. Scholars analyze how Nabokov makes readers complicit in Humbert’s delusions before revealing the truth. The novel appears on virtually every list of twentieth-century masterpieces. Universities teach it in courses on modernism, ethics in literature, and narrative theory.

Brave New World by Aldous Huxley

Huxley’s dystopian vision of a technologically controlled society faced bans primarily in the decades following its 1932 publication. Schools in various countries removed it, citing sexual content, drug use, and disrespect for religion and family values. Ireland banned it immediately for its perceived immorality.

The novel depicts a world where human beings are manufactured in laboratories, conditioned for specific social roles, and kept docile through a pleasure drug called soma. Huxley questioned reproduction, spirituality, and individuality in ways that made censors deeply uncomfortable. His frank discussions of sexuality seemed gratuitous to conservative readers.

Roughly eighty years later, Brave New World reads less like fantasy and more like prophecy. The book’s exploration of technology’s potential to dehumanize resonates powerfully in our data-driven, pharmaceutical-dependent age. What seemed like wild speculation now feels uncomfortably prescient.

High schools worldwide now assign Brave New World alongside 1984 as essential dystopian literature. Students debate whether Huxley’s vision of control through pleasure is more realistic than Orwell’s vision of control through pain. The sexual content that once scandalized barely raises eyebrows compared to the novel’s profound questions about freedom, happiness, and human nature.

The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck

Steinbeck’s 1939 masterpiece about Depression-era migrant workers faced immediate backlash, particularly in California. Kern County banned the book from schools and libraries, calling it obscene and promoting communism. Farm owners and business interests hated Steinbeck’s sympathetic portrayal of workers and critique of capitalism.

The novel’s occasional profanity provided convenient cover for what really bothered censors: Steinbeck’s unflinching depiction of poverty, corporate greed, and labor exploitation. The Joad family’s suffering exposed uncomfortable truths about American inequality. Powerful interests preferred those truths stayed hidden.

Some communities even burned copies publicly. Libraries faced pressure to remove it. Yet the book became a massive bestseller anyway, winning the Pulitzer Prize in 1940. Readers across America connected with the Joads’ struggle and recognized Steinbeck’s moral vision.

Today, The Grapes of Wrath stands as one of America’s greatest novels. It’s taught in virtually every high school. The scenes that once seemed obscene now illustrate Steinbeck’s commitment to portraying working-class life honestly. His blend of naturalism, biblical symbolism, and social consciousness created something timeless. The book that California tried to suppress became essential to understanding California history.

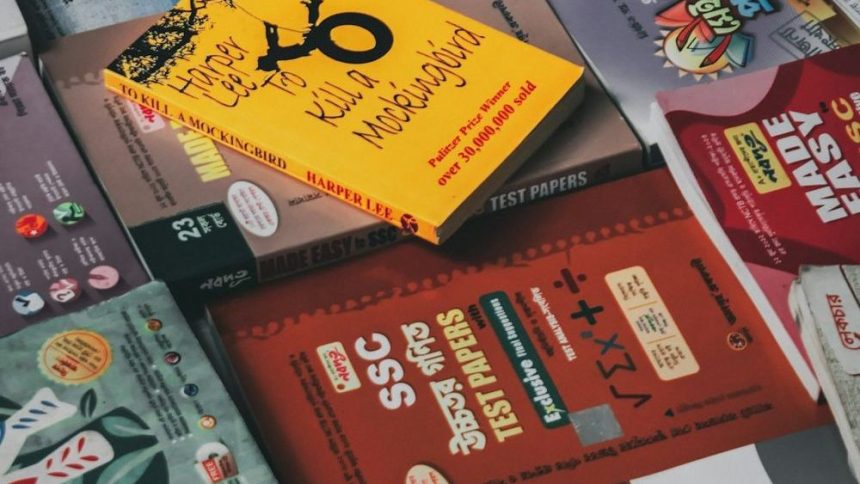

To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee

Here’s the thing: a book about racial injustice and moral courage has been challenged more than almost any other American novel. Since its 1960 publication, To Kill a Mockingbird has faced hundreds of attempts to remove it from schools and libraries. The reasons shift over time, but the impulse to ban remains constant.

Early challenges focused on profanity and racial language. The book’s honest depiction of Southern racism made many readers uncomfortable. Schools in Southern states particularly bristled at how Lee portrayed their region’s history. Later challenges came from different angles, questioning whether the book centers white savior narratives at the expense of Black characters’ agency.

The irony is almost painful. A novel teaching empathy, justice, and standing up for what’s right continues fighting for its place in classrooms. Scout’s journey toward understanding remains as relevant as ever, yet adults keep trying to prevent young readers from experiencing it.

Despite decades of challenges, To Kill a Mockingbird remains one of the most beloved and widely taught American novels. Teachers use it to discuss civil rights history, legal ethics, childhood innocence, and moral courage. The uncomfortable racial language serves an important educational purpose: showing how hatred sounds and why it’s destructive.

Slaughterhouse-Five by Kurt Vonnegut

Vonnegut’s anti-war masterpiece faced immediate censorship challenges after its 1969 publication. School boards objected to profanity, sexual references, and what they saw as anti-American sentiment. The novel’s time-traveling structure and darkly comic tone confused readers expecting straightforward war narratives.

One famous incident involved a school board member burning copies of the book in a furnace. Vonnegut responded with a letter defending artistic freedom and pointing out the absurdity of burning books while claiming to uphold American values. His defense became almost as famous as the novel itself.

The book’s treatment of the Dresden firebombing challenged sanitized versions of World War II. Vonnegut’s refusal to glorify combat or pretend war makes heroes troubled those who wanted patriotic narratives. His phrase “So it goes” repeating after each death seemed flippant to critics who missed its deeper commentary on human mortality and war’s senselessness.

Slaughterhouse-Five now appears on high school and college reading lists worldwide. Its experimental structure influenced generations of writers. Scholars recognize it as essential war literature, precisely because it rejects conventional approaches. The book that was burned in school furnaces now helps students understand war’s psychological toll and the power of unconventional storytelling.

Beloved by Toni Morrison

Morrison’s 1987 novel about slavery’s lasting trauma faced challenges almost immediately, particularly in high schools. Parents objected to its graphic violence, sexual content, and disturbing subject matter. Some argued the book was too complex and dark for young readers.

The novel doesn’t flinch from slavery’s horrors. Morrison depicts physical violence, sexual abuse, and the psychological devastation of being treated as property. A ghost haunts the narrative, representing both a murdered child and the weight of history that cannot be forgotten or easily escaped.

Challenging Beloved often reveals deeper discomfort with confronting slavery’s full reality. The book forces readers to sit with overwhelming pain and understand trauma’s intergenerational impact. It’s not easy reading, but that difficulty serves Morrison’s artistic and moral purpose.

Despite ongoing challenges, Beloved won the Pulitzer Prize and stands as one of American literature’s towering achievements. Universities worldwide teach it in courses on American literature, African American studies, trauma theory, and narrative innovation. Morrison’s blend of historical realism and magical elements created something unprecedented. The novel that some wanted banned transformed how literature approaches historical trauma.

What This Teaches Us About Censorship

The transformation of banned books into treasured classics reveals something fundamental about art and freedom. Attempts to control what people read rarely succeed long-term. Ideas cannot be suppressed permanently, particularly when those ideas speak to real human experiences and concerns.

Every generation thinks it knows better than the last, yet each one tries censoring uncomfortable art. We look back at past bans and see closed-mindedness, but contemporary censorship battles continue. The impulse to protect people from challenging ideas remains strong, even when history shows such protection ultimately fails.

These books also demonstrate art’s power to outlast its critics. Authors who wrote honestly, even when facing condemnation, created works that endured precisely because of their honesty. The courage to challenge norms, explore difficult subjects, and risk controversy often separates forgettable books from lasting literature.

What do you think about these banned books becoming classics? Have you read any of these controversial works? Tell us in the comments which banned book surprised you most or which one you’d recommend others discover.